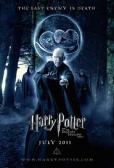

This was the close

“This was the close. This was the moment. He pressed the golden metal to his lips and whispered ‘I am about to die’.” – Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, pg. 559

Any person who held Deathly Hallows and read those words 4 years ago knows that heart-stopping feeling that came with a sharp intake of breath and sudden tears, a moment that truly encompassed the utter helplessness of being a reader: the desire to jump in and change the story combined with the bitter knowledge that you already hold the rest in your other hand. The beauty of Harry Potter was growing up with the characters, opening Philosopher’s Stone to find that Harry turned 11 at the same time that you did, and Hermione’s wild hair and awkward appearance mirrored your own. As we matured and aged, so, too, did the books, launching from simple and cautiously curious to larger, more in-depth, and complex. By the end of the series, Potter readers had delved into highly philosophical themes, learned the importance of courage, the power of Love, the necessity of redemption, the definition of personal identity, and the signficance of friendship — and acquired some Latin along the way. There is an inherent sense of understanding amongst Potter fans that is indescribable to others — when we talk about the books, we just know. We understand it in a way that generations who start it now never will, because we grew with it; we awaited Harry’s next adventure with trepidation and a crippling curiosity. We sat at our kitchen tables or under our covers or on our couches or read with the novel hidden discreetly inside our school desks, devouring the book we went to the Indigo midnight release party to buy. We spent our time inbetween books reading FanFiction stories, looking for updates on J.K Rowling‘s website, buying merchandise, and decorating our rooms in Gryffindor memorabilia. Closing the chapter on the Harry Potter decade was much like finishing the last chapter of Book 7; a mixture of emotions washed over me, from sad to happy to understanding and, finally, a desire for more. Yesterday, I saw the last Potter film, which was, incidentally, the birthday of J.K Rowling — and the boy who lived, himself. This time, however, I had hoped for more plot.

Any person who held Deathly Hallows and read those words 4 years ago knows that heart-stopping feeling that came with a sharp intake of breath and sudden tears, a moment that truly encompassed the utter helplessness of being a reader: the desire to jump in and change the story combined with the bitter knowledge that you already hold the rest in your other hand. The beauty of Harry Potter was growing up with the characters, opening Philosopher’s Stone to find that Harry turned 11 at the same time that you did, and Hermione’s wild hair and awkward appearance mirrored your own. As we matured and aged, so, too, did the books, launching from simple and cautiously curious to larger, more in-depth, and complex. By the end of the series, Potter readers had delved into highly philosophical themes, learned the importance of courage, the power of Love, the necessity of redemption, the definition of personal identity, and the signficance of friendship — and acquired some Latin along the way. There is an inherent sense of understanding amongst Potter fans that is indescribable to others — when we talk about the books, we just know. We understand it in a way that generations who start it now never will, because we grew with it; we awaited Harry’s next adventure with trepidation and a crippling curiosity. We sat at our kitchen tables or under our covers or on our couches or read with the novel hidden discreetly inside our school desks, devouring the book we went to the Indigo midnight release party to buy. We spent our time inbetween books reading FanFiction stories, looking for updates on J.K Rowling‘s website, buying merchandise, and decorating our rooms in Gryffindor memorabilia. Closing the chapter on the Harry Potter decade was much like finishing the last chapter of Book 7; a mixture of emotions washed over me, from sad to happy to understanding and, finally, a desire for more. Yesterday, I saw the last Potter film, which was, incidentally, the birthday of J.K Rowling — and the boy who lived, himself. This time, however, I had hoped for more plot.

The film was brilliantly executed, its special effects superb, and its depiction of the final battle emotionally-charged. The scene at Gringotts with that poor dragon had me on the edge of my seat and holding my breath, even though I knew what was going to happen. Most notably, David Yates’ construction of The Prince’s Tale — that is, the memories of Severus Snape — was beautiful and touching. Alan Rickman’s performance caught me completely off-guard, catapulting from the morose and macabre Snape to a broken, devastated man. Throughout that scene, and the shocked silence in the seconds following it, not a sound could be heard in the theatre other than the emotional sniffs and loud gulps of people trying to maintain their composure. This, truly, was a part that I actually felt more connected with in the film than the book. Film is a different language than Literature, its images often allowing us to establish a sentimental connection with the characters in a way that words cannot.

The film was brilliantly executed, its special effects superb, and its depiction of the final battle emotionally-charged. The scene at Gringotts with that poor dragon had me on the edge of my seat and holding my breath, even though I knew what was going to happen. Most notably, David Yates’ construction of The Prince’s Tale — that is, the memories of Severus Snape — was beautiful and touching. Alan Rickman’s performance caught me completely off-guard, catapulting from the morose and macabre Snape to a broken, devastated man. Throughout that scene, and the shocked silence in the seconds following it, not a sound could be heard in the theatre other than the emotional sniffs and loud gulps of people trying to maintain their composure. This, truly, was a part that I actually felt more connected with in the film than the book. Film is a different language than Literature, its images often allowing us to establish a sentimental connection with the characters in a way that words cannot.

There are times, however, when the language of Film cannot accurately convey the complicated cloud of details surrounding characters and relationships in the brilliant way that a book can. Though I loved the film, there were a few things that I wish Yates and his team had stayed true to. For example, Neville’s character should have been as celebrated in film as it was in the book. He has a few seconds of fame — blowing up the bridge, speaking out in front of Voldemort, bringing Harry, Ron and Hermione back to the Room of Requirement — but they all seem to be construed as comic relief. In each scene, there is some forced comedic dialogue: he says “Well, that went well”, after the bridge scene, Voldemort’s supporters jeer and laugh at him when he speaks up, and he is quickly overshadowed in the Room of Requirement. Most disappointing was the crew’s complete dismissal of Neville and Harry’s prophetic alignment, and Neville’s personal trajectory and honour in killing Nagini. I realize that it is a film, and there is not enough time to illustrate everything in the book, but the directors did not seem to consider some of the most important elements of the story, choosing to concentrate on the action instead. That scene should have been poignant and isolated, but instead it moved rather quickly and he was hardly concentrated on.

While I know some people did not like the comedic relief of the film, I actually enjoyed it — like the book, it has dark themes interspersed with optimism. For example, in the book, after destroying Helga Hufflepuff’s horcrux in the midst of battle, it is described:

“It was nothing,” said Ron, though he looked delighted with himself, “So whats new with you?”

In that way, the film’s comedic relief DID reflect the book’s style. But I was disappointed that the moments with Fred and George seemed rather contrived. Before the battle, the camera shoots George saying, “Ready, Freddy?” Fred nods, and that’s it. They do not capture the moment of his death, or the last laugh on his face, as the book did. We lose its importance.

Further, Molly Weasley would not have smirked after killing Bellatrix, as she did in the film — it was a serious, intense moment in the book, a death that mirrored her cousin Sirius’, one that should not have been played out like a “ha-ha” moment. What struck me the most was Harry’s utter lack of regard for Ron upon his decision to die; he hugs a sobbing Hermione with fervor, yet does not even glance at Ron before he leaves. It did not feel right. Lastly, Voldemort’s weird and crazy laughter after “killing” Potter, the uncomfortably awkward hug with Draco, and the theatrical hand movements actually made me (and the rest of the theatre) burst into laughter, ourselves — it was just strange. The presentation of Potter’s body should have been as dramatic and emotional as it was in the book.

Further, Molly Weasley would not have smirked after killing Bellatrix, as she did in the film — it was a serious, intense moment in the book, a death that mirrored her cousin Sirius’, one that should not have been played out like a “ha-ha” moment. What struck me the most was Harry’s utter lack of regard for Ron upon his decision to die; he hugs a sobbing Hermione with fervor, yet does not even glance at Ron before he leaves. It did not feel right. Lastly, Voldemort’s weird and crazy laughter after “killing” Potter, the uncomfortably awkward hug with Draco, and the theatrical hand movements actually made me (and the rest of the theatre) burst into laughter, ourselves — it was just strange. The presentation of Potter’s body should have been as dramatic and emotional as it was in the book.

I didn’t hate the movie — I really did enjoy it and would definitely see it again. I just felt that there were so many things (from the first movie) that they should have included and rethought. One thing that the films accomplished was its wonderful portrayal of the Story of the Three Brothers — not only with the Burton-like depiction (see below), but also the intertwining of Voldemort, Snape and Harry’s story. In the book, before Harry greets death, he speaks of Hogwarts: “But he was home. He and Voldemort and Snape, the abandoned boys, had all found home here.” The Story of the Three Brothers is played out in them: Voldemort, the one who died for Power, Snape, the one who died for Love, and Harry, the one who greeted death as an old friend.

JK Rowling had no idea she would change the world after the release of the first book on June 30 1997, possibly one of the most historically significant dates in the world of Literature. 13 years later, we still love the Boy who Lived, and his story that forever will.

Mischief managed.